5 reasons to stop asking successful people how they became successful

SFE: Safe Failure Environment, Part 1.

This is the first article in a series I’m writing about the importance of failure. More specifically, the importance of safe failure.

In order to get to why failure is so important, we first have to consider the cult of success, and what’s wrong with asking successful people how they became successful. If an interview with you wouldn’t be published in a magazine, then you probably aren’t successful enough to be the target of this article’s criticisms - let’s say top .1% is our line.

This article is a criticism of interviews which highlight anecdotal evidence from the successful as wisdom to be followed. Bo Burnham puts it well when he gets asked what his advice to young people is:

Problem #1 with asking the successful how they did “it”:

They got lucky.

In a sufficiently large population someone is bound to get lucky and win the lottery, yet it’s ridiculous to think someone might ever go around and interview lottery winners about their strategies for winning lotteries.

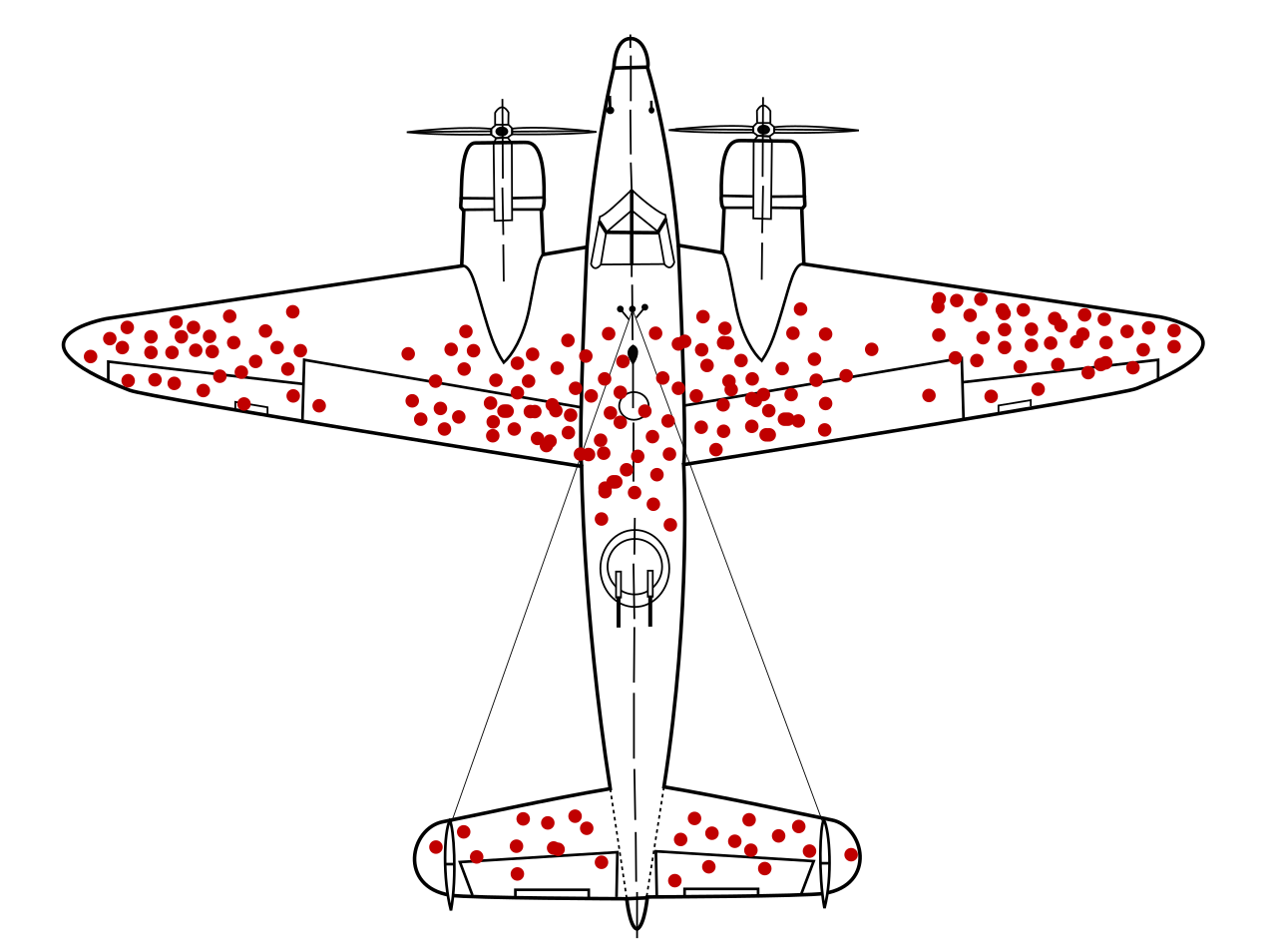

The classic survivorship bias example is bullet holes in airplanes: you might initially think to reinforce the sections most often damaged on returning military aircraft, but this is counterintuitive. The fact that the planes survived with the damage indicates that this damage was survivable. Instead, we should reinforce the areas that show little damage on return of the aircraft since the aircraft that were damaged in those areas crashed. All of the planes went out with rudders, wingtips, and engines; but only the lucky planes that kept the engines returned.

Think of the returning aircraft as successful entrepreneurs, and the aircraft that don’t as failures. If you only pay attention to the successful entrepreneurs, you cut off the part of the population that actually contains the relevant information to success: what critical pieces are necessary to avoid failure.

Demographic studies start to take on an even-more-grim tone when viewed through the lens of survivorship bias. When we look for bullet holes on the wings of surviving politicians and businessmen, for example, the critical pieces of functionality look a lot more like “white, male, rich” as opposed to “hardworking, diligent, intelligent”. All of the individuals went out hardworking, diligent, and intelligent, but only those of them that were also white male and rich returned.

This is probably going to be the hot-button take of the article, but I’m going to say it anyways: The worst people to ask for advice on how to succeed in a field are prodigies and instant-successes: their first scratcher was a winner; they have never lost a coin flip.

Problem #2 with asking the successful how they “did” it:

They don’t know.

Even if a survivor recognizes they got lucky, they often don’t have the context to know why they succeeded and others failed. They can only gain that context through also experiencing failure. In fact, the trustworthiness of survivor opinion goes up the more times they have failed.

Take higher-ed admissions as an example. Would you rather receive advice from someone who had been admitted to a Harvard MBA on the first try, or someone who had been admitted on their sixth attempt? The person who got in first try has only one single point of data- they don’t know whether they received the admit because they happened to be superfans of the same sports team as their interviewers, or because they wrote an emotional and compelling admissions essay. The reject, on the other hand, can at least tell you about the time they got rejected despite the nerding out over sports on their interview.

The more time we spend failing, the more context we gain. Trial and error allows us to select and eliminate irrelevant details over time. It will never be perfect, and there will always be an element of luck, but at least those who failed first have more available information from which to reason. Knowledge requires context to be useful. The longer someone spends “succeeding” the further detached they become from providing advice to relevant upstarts on how to avoid pitfalls.

We’ll see in part 2 how this isn’t exactly 100% true, and why a healthy non-failing state is actually necessary to create the safe failure environment needed to learn. For now, though, what matters to us is that time spent succeeding is time not spent failing.

Bikeshedding break:

“But coin tosses and lotteries are games of chance! War, college admissions, and business are games of skill, determination, and hard work!”

Ah, the merit myth. As I said before, given a sufficiently large population, someone has to succeed. Let’s say that lucky sonofagun does know exactly why they succeeded. Why would they share their secret and threaten their own position with competition? Furthermore, what if they achieved success in an unscrupulous way? What if it wasn’t luck, but something more insidious?

One only needs to start looking at how many celebrities are related to other celebrities to form a picture of how little merit actually enters into the equation. A favorite game of mine is “which starving artists actually had a trust fund?”

Talent does definitely exist, but we suck at testing for it unless it’s measurable (hold your breath for ten minutes) or visible (do a triple backflip). Everything else needs to be operationalized to be verifiable, and people have been skirting those systems and inbred metrics since the dawn of society.

Hence we come to the third problem with asking the successful about their success: They have no incentive towards honesty.

Problem #3 with asking the successful “how” they did it:

They have no incentive towards honesty.

If someone became successful unscrupulously, they aren’t going to tell you that when you ask them. We don’t have very good ways of checking who ended up at the top through merit, and who ended up there through foul play.

Speaking of, how do we even know what is and isn’t foul play?

I was once advised by a stock broker to simply “report my earned income after brokerage fees.” To my idiot ass, they were suggesting tax fraud. What they were actually suggesting is adding the fees to the cost basis of the transaction, which isn’t tax fraud. I just didn’t have the context to understand what was sloppy communication on the part of an expert. This brings us to number four:

Problem #4 with “asking” the successful how they did it:

You don’t have enough context to understand their advice.

Remember how I said earlier that knowledge requires context to be useful? Well, that counts doubly for the learner. One of my favorite interview questions is asking someone to serially explain a concept to different audiences:

I’m a kindergartner, explain calculus to me

Alright now I’m a construction worker

Alright now I’m an alien who has never seen a human being before.

Alright now I’m your boss.

It’s really useful to see how someone approaches and deals with theory of mind.

People engage in subjectivity bias constantly: they fail to recognize you lack information they are privy to, they excuse away their failings while punishing others, they assume your goals are identical to theirs. Just because someone is an expert in chess doesn’t mean they are an expert in communication, so be wary of taking the words of the successful as gospel.

Problem #5 with asking the “successful” how they did it:

They occupy a local maxima.

Today’s success is tomorrow’s tragedy. We inform success through relative context. A chimp is more successful than its peers if it can reproduce more than the others, but globally unsuccessful if its effort to feed all its children spread resources too thin and they all starve.

You have no way of knowing what point on the curve you occupy. Here’s an interview from April with a dogecoin millionaire. It hasn’t aged well.

Of course there’s a difference between asking a dogecoin millionaire and a tested executive about how they do what they do. But even the executives can fall from grace. QT Wiles was a Silicon Valley golden boy, giving plenty of interviews and being lavished with praise for successfully piloting Miniscribe through economic downturns unscathed. If you know the story, you know that QT Wiles also committed one of the largest single instances of fraud in history by ordering managers to falsify inventory by passing literal bricks off as hard drives. If you don’t know the story, give it a gander, it’s fascinating:

If we’re being ligural: Man, I got a hard drive in the mail from Miniscribe, but I think it’s a brick.

Conclusions

Stop asking successful people how they did “it.” If you must, ask a successful person who failed a bunch before they became successful. Seriously, the more, the better. You want a real underdog story here.

This is the first piece in a series dedicated to my life’s greatest work: failure. We learn more by failing than we ever do by succeeding. Argue with me in the comments or on twitter (@laulpogan) about that statement all you want, there will be another installment and ode to failure coming hot off the presses soon. Share this one with your buds so you’re all ready for it.

Followup

This article is about the dangers of taking anecdotal evidence as gospel without thinking about how its source got to the position of success they occupy. Some readers in the comments on reddit have rightly pointed out that controlled surveys of successful individuals to find commonalities have merit. I wholeheartedly agree! I think this merits another article with a deeper investigation, so if you have examples of such successful-feature-roundups, please comment them or send them my way!

This is pointless drivel. As someone who's met thousands of people writing credit, I can tell you this. All of your points are wrong. Not only do they know, they can tell you what they failed at and overcame. What they still worry about despite their success and a general defensive financial posture to take risks. Suggesting it's luck devalues the planning and decision making of the individual and ignores the fact that those of failed likely didn't have the problem solving skills to overcome. Your outlook is entitled. Which is what everyone who thinks wealth is handed to those who are "Lucky" the reality is wealth comes to those who work hard and focus on the right things.