Fedora Friday

Hi there, and welcome to Engineering Our Social Vehicles. I’m your host, Paul Logan. Today is Fedora Friday. If you’re new to the newsletter, that means that on Fridays ‘round these parts we like to talk about famous fedoras. Today, we’re going to talk about The Semiotics of Silly Hats.

Silver Pass

When it rains continuously for days on end in the backcountry, you hit a point where everything you own is “soaked through.” You end the day staring down your wrinkly little piggy toes in between replacing your waterlogged socks with a damp pair from your pack to sleep in.

I had been storming for 3 days straight when we saved Charlie from falling off a waterfall on the way up to Silver Pass. Here’s the ever-so-lovely Pain Perdu walking through the waterfall in question about 5 minutes before the incident. You can see McQueen, her husband and all-around awesome dude (who was featured in The Crest) come up right after:

As you can tell, we were all well and truly soaked. When you’re that soaked and it’s still raining, you really only have one recourse to get dry: fire. In the Sierra, one of the catches with fire (ha) is that you shouldn’t have a one above 9,000 feet. We got Charlie settled at about 9,100 ft., and were within spitting distance of the pass itself.

Even though there’s no service in the backcountry, thru-hikers still use an app called farOut as a trail map to check water sources, campsites, etc.

Silver pass is 9,855 ft tall. It is the last pass of a week long backcountry section of the Sierra, so getting over it felt like slaying the symbolic dragon lying between us and much-deserved town food.1 FarOut placed the first fire-safe campsite at around 2 miles and 1,000 feet down from the pass itself- we decided to push for it.

The storm broke and the sunset dipped under the cloud cover as we came down from the pass, which made for some gorgeous views. Here’s me recounting the whole episode as I hustle my lil bootie off trying to make that campsite before dark so I can set up a fire:

It was well and truly dark 40 minutes later when I turned the bend to see the campsite, a big fire already burning. Shit.

On the trail it’s a coinflip as to whether someone will view it as polite to ask to share a site, since it can quickly turn a comfortable, serene camping spot into a cramped frustrating mess. We had been hoping this one would be empty. No such luck.

Exhausted as I was, I built up the courage to ask if they might share their fire with some weary fellow travellers. I debated and rehearsed the most diplomatic way to broach the subject as I weaved my way down the switchback to the site.

“Hey all- I’m sharing your fire and I’m not taking no for an answer.”

“Hi friends- mind sharing your fire?”

“Hey! I’m soggy and I just saved a guy’s life- would you be so kind as to share you fire?”

*Wordless walk into camp and begin to dry feet on the fire*

Mind racing as I entered the clearing of the fire, I opened my mouth to speak and was immediately cut off before I could when someone shouted my trail name:

“Heaves?!”

Heaves’ Hats

The campsite was full of people I’d never met, but who somehow knew me by my dimly lit profile. I should explain:

In the desert, I was gifted a Baggu Collapsible Sun Hat.

It quickly became my favorite piece of kit. To the degree that I gifted my original black hat to my friend Cinderella when he joined me on trail in the Sierra, and bought a new lavender one. That hat is the inspiration for EoSV’s color scheme.

The giant purple hat became my trademark on trail, in the same way that wearing a dress became my trademark in town. See a guy in a dress or with a giant purple hat? Yep, that’s Heaves.

So, when I walked into that campsite the giant floppy disk of my hat alone marked me. The hikers who had built the fire were my friend Cinderella’s trail family. He’d told them about me, and they’d seen him wearing my former sun cover. Even in the dark, they knew my instantly by my silly hat.

The Ministry of Silly Hats

Religions have been leveraging the value of decorative hats since long before I walked into that campsite. Across the world special hats separate men from boys, devout from gentiles, and clergy from congregation. Hats have a funny way of shaping to hierarchy, such that we know popes from bishops from cardinals from priests from nuns.

It seems that hats started out as a functional cultural adaptation- used to protect heads, keep them warm, keep them shaded, and keep them safe from lice. Convergent social evolution deposited each culture with its own specific ceremonial and institutional headgear.

Most cultures reverse-justify the symbolism of hats and caps. For example, the Talmud teaches that the Kippah exists to remind its wearer of their relationship to God, yet it’s more likely that the hat originated from the same source as the Catholic zucchetti: to protect bald spots from the sun.

Overwhelmingly, if a hat isn’t meant to do a job, it’s meant to mark importance: whether of an occasion or of a person. Often times the hat accompanies a uniform, but the two serve as redundant markers of the same status, and can be recognized independently of one another. If you’re like me, your brain can fill in the blanks to imagine a uniform with the prompt of these hats alone:

Vice-versa, if shown uniforms you could probably imagine the hats. Incredible pattern matching machines that our brains are, hats have developed as a secondary language used to signal social significance, function, and rank.

Why silly hats?

Hat’s require very infrequent laundering.

They represent the smallest amount of fabric to customize a uniform.

They are the first visual marker in line of sight.

They increase the height of their wearers.

They form a non-semantic, visual marker in memory.

They provide an immediate contrast between members of a hierarchy.

The passively indicate purpose, specialness, and significance.

Individuals who made hats iconic

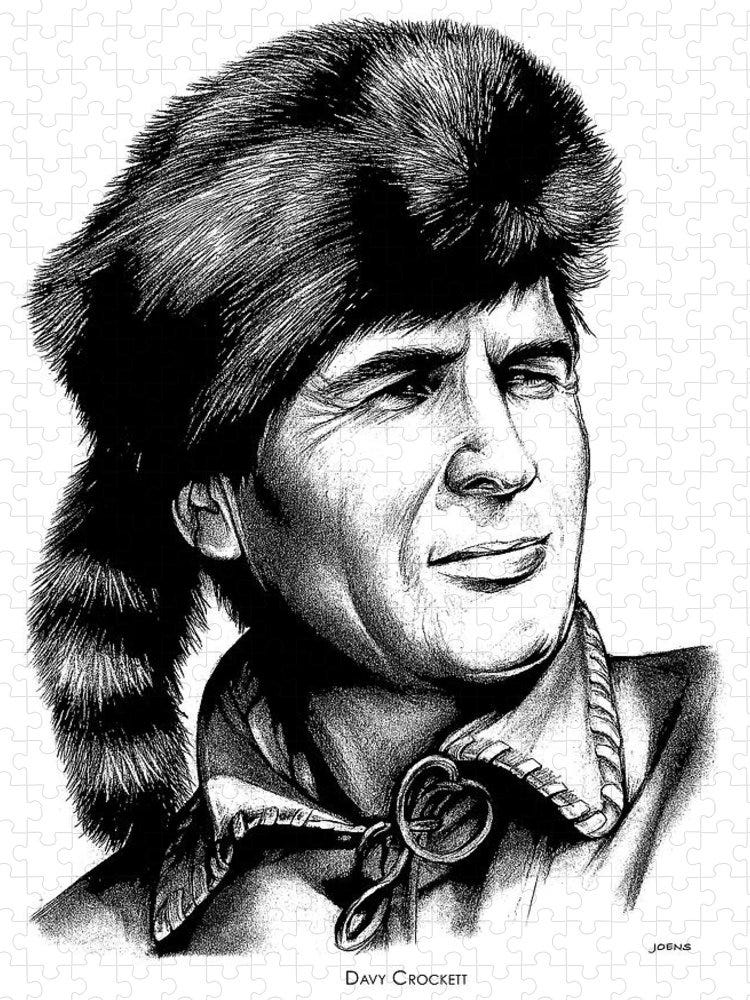

There are plenty of people who made history. There are relatively few who did it all while wearing the same hat. Not everyone in this list was associated with their iconic style of hat while alive. Crockett, for example, only started wearing his coonskin cap after his popularity had begun to wane. All of these individuals understood the psychological power of silly hats, and used it to their advantage.

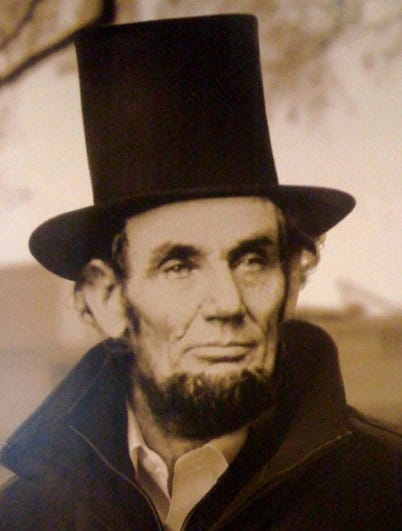

The Licoln-Stovepipe.

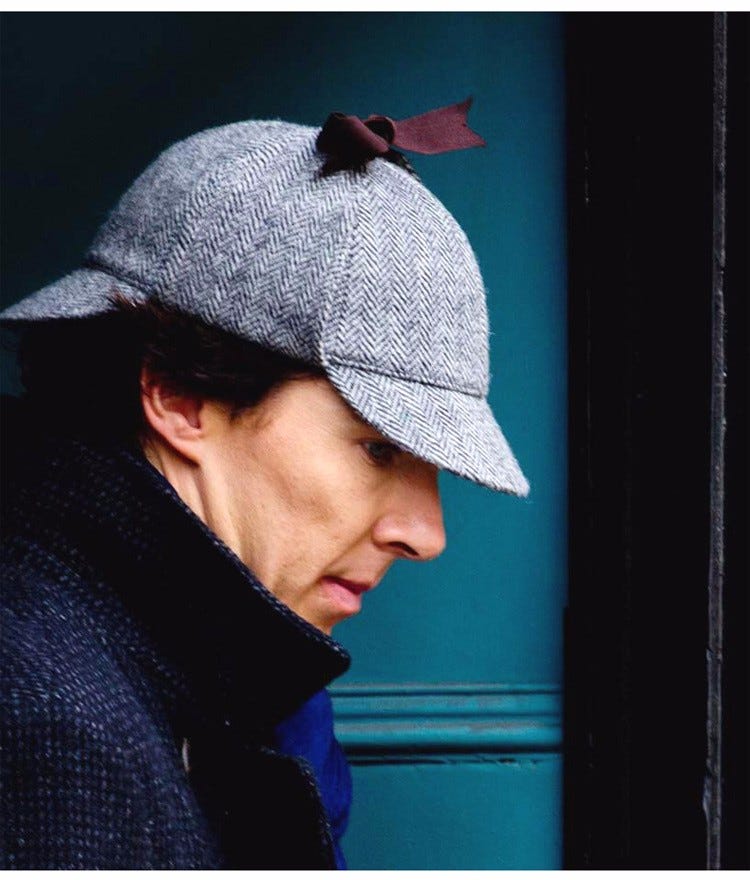

The Holmes-Deerstalker.

The Sinatra-Fedora.

The Keaton-Porkpie.

The Kennedy-Pillbox.

The Churchill-Homburg.

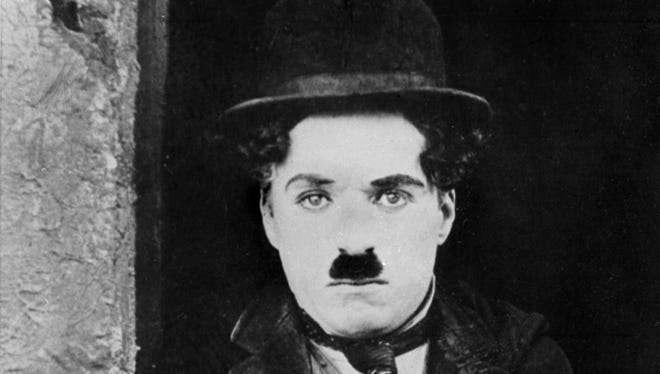

The Chaplin-Bowler.

The More-Bonnet.

The Bonaparte-Bicorne.

The Crockett-Coonskin.

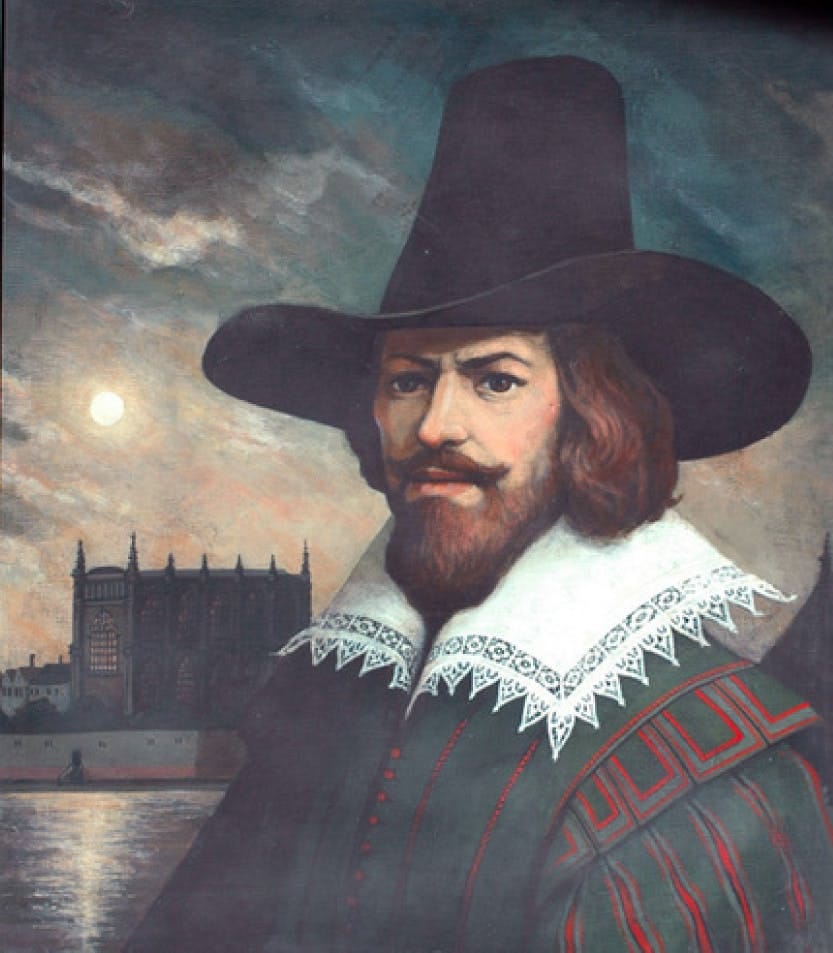

The Fawkes-Sugarloaf.

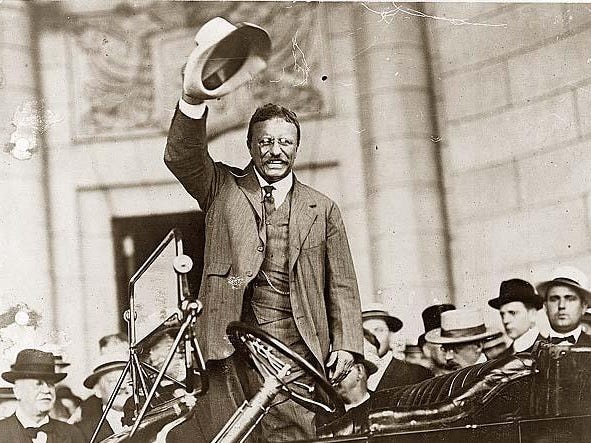

The Roosevelt-Panama.

The Marley-Rastacap.

I’m making a bid for it with my sun hat. I even bought a third one when I got off trail. Dog owners in the park will sometimes refer to me as “the guy with the big floral hat.” And you know what? People often know who they are talking about.

Hats that make individuals iconic.

Like I said earlier- where hierarchy forms, hats seem to follow; God help us if it’s the other way around. These are hats that let even the uninitiated know that someone has a role they are playing within an organization, and should be left to perform that role:

Chef’s Hat

Bearskin Hat

Captain’s Hat

Barrister’s Peruke

Policeman’s cap

In addition to role-based hats ceremonial hats mark days like graduations and weddings. If you’re in a foreign culture and someone is wearing a particularly elaborate or silly hat, you can make a safe guess that they are either doing an important job or in the middle of an important day, or both!

Conclusion

A social philosopher who I can’t currently remember the name of once said “a perfect society is one in which no one knows who their parents are.” I disagree. An ideal society is one in which everyone wears an appropriate silly hat. Don’t cross me on this, I’ll fight you- and I won’t take off my big floppy hat first; so it will probably hit you in and about the face and eyes. That’s what you get for bringing words to a hat fight.

I remember thinking ceaselessly about drinking a continuous stream of Mr. Pibb.

This is a terrific and funny essay. I hope I win a hat!,