Face-planting and laughing about it: why we need to encourage failure in learning.

SFE: Safe Failure Environment, Pt. 2

Hello! Welcome to my second article dedicated to my life’s work: failure. Yesterday we talked about the problems with overfocus on success.Today we are going to talk about safe failure.

What is “safe” failure? Safe failure is failure that has no negative repurcussions. A safe failure environment is one in which learners can expect to experience minimal- if any- repercussions for mistakes. This is in contrast to an unsafe failure environment, in which learners can expect to pay a high cost for any mistake they make.

In this article, I’ll detail why imitation learning leads us to make unnecessary additions to our early methods which then must be removed through trial and error. I’ll discuss how we learn, why the process of trial and error works better in safe failure environments, and why learning and performance are better facilitated in them.

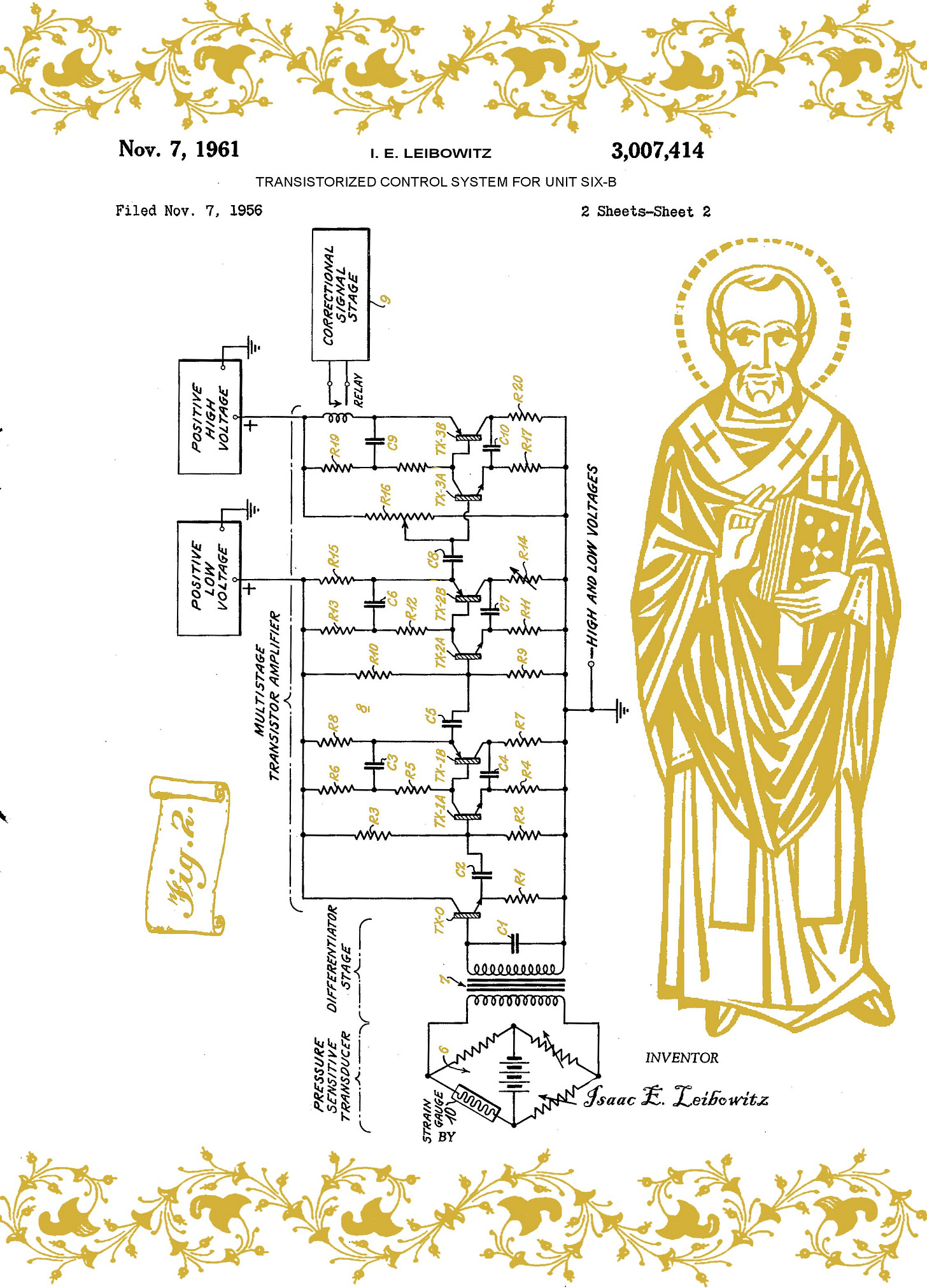

Transistorized Control System for Unit Six-B

A Canticle for Leibowitz is a dystopian sci-fi book about a benedictine order of monks. They were founded by an engineer from the last civilized generation before a nuclear holocaust and a “Great Simplification” wherein luddites killed all the literate and burned all the books.

The book mostly takes place in a monastery dedicated to the preservation and study of ancient (for us contemporary) knowledge. It being a monastery, the monks do what they do best: copy and illuminate manuscripts.

Early in the book, a monk discovers a “sacred” document from the founder of the order himself- a blueprint entitled “ “Transistorized Control System for Unit Six-B.” This monk could never condescend to understand the ways of the holy ancients, and as such replicates the document in its entirety- down to the color.

“There must be a reason the ancients chose this color scheme, but it’s beyond me. What a shame it wastes so much ink.” He muses to himself while copying the document.

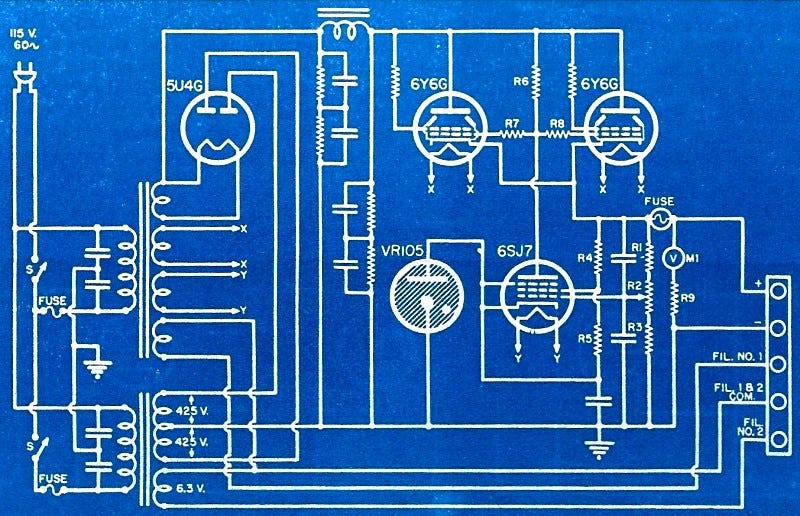

Why so blue?

Ever wonder what made blueprints blue in the first place? They were an early application of cyanotyping, which allowed engineers to take quick and accurate negatives of documents.

Later on, our monk discovers in another text that the blue-white color scheme is a byproduct of this forgotten negative-taking technology. It is irrelevant, a spandrel (see Conformity, Pt. 2).

Our monk is predictably embarrassed by the monastery’s centuries-long waste of ink. However, he soon cheers up when he realizes how much faster he will be able to work now that the color doesn’t need to be reproduced. He even decides to illuminate a copy of the diagram with all that extra space and time.

The Process

Behold, the process of learning! Trial! Error! Progress.

Improving at a skill is a process of combined imitation, emulation, and trial and error. Humans begin by copying the form, as opposed to chimps, who attempt instead to emulate the desired results. While we can’t point to a discrete reason for the difference, some guess that since those we copy have already filtered action by optimizing for result, there’s benefit to selecting for imitation over emulation .

A perfect copy, however, is a stupid copy. As undiscerning as it is holistic: it captures relevant and irrelevant details alike, just like our monk. A photograph is a perfect copy, but a camera is useless without a photographer who has the context to photograph the relevant scene.

With authority, we copy through imitation. An instructor demonstrates the proper technique to achieve a desired result, we attempt to replicate it, and then they correct mistakes or irrelevant capture in the replication. We get immediate feedback when we achieve a desired result, but still need input from authority to let us know if we arrived at it in the incorrect fashion. Instruction allows us to shortcut the self-reflective step by substituting our own untrained error-checker with that of a trained authority’s. Even with instruction, however, the important part is the correcting and removing of errors in our imitation, since successful emulation is often self-evident in the results.

Without authority, we’re stuck on emulation and trial and error. We rely on outcome to inform our skill in execution. First, we emulate: create the best model of action we can imagine for achieving a desired result, then recreate the model to the best of our ability in reality. We check our results against the ideal, accomplished state, and the difference yields errors which we can use to adjust the model. Initially, our stupid model yields poor results in emulation. Those poor results give us context to figure out which elements of our model were relevant, and which were spandrels, like the blue paper of a cyanotype. Think about it like the process of a sculpture chipping away stone to reveal art.

Thanks to the internet, there exist a lot of states in between having and instructor and being stuck in the middle of the woods with a hatchet. Whether you find yourself under tutelage or underwater, it’s important to remember that there is a motivational component for which success is very important, but that it merely pushes us to continue the process of learning. The process itself is all about error and reflection.

Unsafe Failure Environment

Hatchet is the perfect example of being put in a position where failure is intolerable if not fatal; an unsafe failure environment. It’s an incredible story that derives dramatic tension from the nagging feeling that this boy should have died when he ate those poison berries.1

The problem with learning that focuses on success is that success is a poor teacher when it comes to eliminating the inefficient. If you succeed, there is no immediate incentive to cut spandrels. No reason to optimize save to improve. If you’re in the middle of the woods with no lifelines there’s a limit on the number of mistakes you can make before you just outright die, and time spent improving processes that already function is time not spent figuring out how to fix vital ones that don’t.

If you fail, there is immediate incentive to refine, optimize, simplify - without doing so you cannot proceed. The more mistakes you’re able to make, the more context you have for what are necessary components to success. That’s why it’s beneficial to be in a situation where you can afford to make as many mistakes as you want. Organizations with higher tolerance for mistakes see better performance when compared to organizations that favor punishment for error.

Learning environments that create an expectation of success without ever providing the opportunity for safe failure are bad ones. Take the American educational system, which has kluged performance and participation into the same inbred metric by including early mistakes in the overall mark for the course.

This sends the wrong message: that in order to be competitive, one must be perfect from the beginning. I’ll note that the argument could be made that the punishment of getting a bad grade motivates students into trying harder like some sort of corrective self-diagnostic via shame/pain. However, the same reasoning falls flat in testing with corporal punishment, and other studies around reward suggest that success is extremely important in motivating students to keep learning.

An alternative to this system is the UK, where marks are determined entirely by performance on the final exam. Of course, betting everything on a single exam has its own set of problems, but it doesn’t punish the process of learning itself. The UK system even expects mistakes- with the score for a 1st (best marks) often starting at 70%.

Form, (Brute) Force, Finesse

My friend Alexia started skiing about a year after I did. She is now much better than me.

Every time I allowed myself to be tempted by more experienced skiers into a run above my skill level, she stayed behind in her comfort zone. I often times found myself in the middle of steep slopes unsure of how to get down; terrified of hurting myself, cursing the brilliant skiers I had the hubris to think I could imitate. I often did hurt myself, and as a result missed out on large parts of the season. Alexia fell just as much as I did, but she fell in places she was comfortable, and she never got injured.

I was, predictably, a slow study. When I did manage to make it off of runs beyond my skill level, I found I had spent more time focusing on not dying than correcting my form. I’d spend my runs hurling myself out of the way of one rapidly approaching obstacle after the next, panting and struggling to see as my rapid breath fogged my goggles. Sometimes I would lash out in frustration at friends trying to offer constructive criticism due to the stress of trying to make it down the mountain alive.

In contrast, Alexia never seemed stressed when skiing. She always seemed happy, even when she fell, and always had the emotional bandwidth to take on new advice. Eventually she was able to convince me not to go on the harder runs with my more skilled friends, and instead stick around the easier slopes with her.

Only when I started skiing in my comfort zone did I realize how many of my movements were unnecessary and exhausting. I often felt I was hauling my entire body into a turn, and hauling it back out. With newfound comfort came newfound confidence. I experimented in ways I never would have on the steeper parts of the mountain. This led to me face-planting into lots of snow, but the falls were gentler, and I stopped fearing them as much. I learned to come up laughing.

Over time I shaved off the rough edges: hinged at the hip instead of leaning my whole body down the slope, loosened the boots in the right places to make them comfortable enough to wear at length, learned to use the shape of the ski to steer into the turn, rather than forcing it with every muscle in my body. All of these changes caused many crashes before they solidified into proper form.

This winnowing was a process of combining laziness and reflection to yield optimization. I wanted to work less so I could have more energy with which to perform. I didn’t see any of the errors, the falls, the practice as hard work: I was just goofing off and having fun, and seemingly getting better while doing it.

This is the joy of finesse. I found it by tossing wrenches into my brute form, not pushing headlong & headstrong into ever increasing difficulty.

Conclusion

We must foster environments where students learn it is OK to fail, otherwise they will never narrow down what factors contribute to success and failure. Fear of punishment distracts from the process of learning and damages performance. High cost of failure makes experimentation to identify and eliminate irrelevancies in functioning processes too risky. Highlighting failure makes it easier to celebrate the small successes that keep us motivated on our way to improvement.

When I changed my environment from one of unsafe failure to one of safe failure, I began to learn rapidly. More importantly, I learned to love an activity I had wanted so dearly to love; but that always seemed to leave me injured or frustrated. I found satisfaction in the small silly mistakes I was able to work to correct, rather than the large defeats I pushed myself into prematurely.

Housekeeping

As always, thank you for tuning in to EoSV, please tweet questions to me @laulpogan, and consider sharing the article with your friends if you found it thought provoking. If you really liked it, consider becoming a free subscriber. You’ll be the first to know when the next article in this series is released.

I’ll probably write about this in a future blog post, but I found out the hard way that not being able to keep water down in the backcountry is a one way ticket to deathtown. Hence my PCT trail name of “Heaves” (as in “dry heaves”).